“Prescription without diagnosis is malpractice.”

– Unknown

What Financial Planning Is Not

I am surprised to have run across so many financial professionals who seem to mix up the terminology on this, so I felt it important to cover what financial planning is and what it isn’t.

Financial planning has little to do with portfolios and their allocation, and a true financial plan is devoid of incorporating portfolios (though it does include the assets themselves) and Monte Carlo simulations in planning software.[1] The software you might have used for this, in most cases, does not fully comply with FINRA Rule 2214, anyway.[2]

What most financial professionals are delivering to their clients is retirement planning, where they would determine goals, identify total income, deduct expenses, and implement a portfolio that they would then manage toward the end goal that had originally been set.

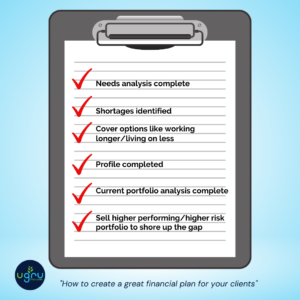

This is a highly problematic approach for you and your clients because it prevents critical financial issues from being identified. The essence of the relationship ends up in a rinse and repeat cycle that looks like the image below.

Magic show complete.

This is investment planning methodology, not financial planning. Because of this, the value proposition your clients are starting to hear is: Give me all your money, pay me to manage it, and in five years, we’ll see if that was a good decision.

What Holistic Financial Planning Is

Holistic financial planning is all-encompassing. It is a process that considers all aspects of the financial household and will likely require a quarterback or a guide, someone like an advisor, agent or the right financial coach to guide their client with the proper software as a self-discovery process.

UGRU has a great planning software, Retirement Destinations™ that makes even the novice financial professional look masterful in their planning capabilities (think TurboTax for financial planning).

As a financial professional, you must take the lead of your clients total financial picture so that the decisions made are the most optimal relative to every other nuanced financial element. In the end, one thing matters more than anything, and that is to have a clear picture of where your client stands and where they are going no matter where they are in their financial journey.

The only way to accomplish this is through:

- Establishing goals

- Identifying current resources

- Identifying current courses of action

Then go through a category-Iterative process on each current and possible financial decision in all the following areas (though not necessarily limiting yourself to these):

- Investment real estate

- Primary residence

- Debt structure

- Estate planning

- Tax planning

- College planning

- Distribution planning

- Alternative investments

- Business planning

The end goal is to identify and ultimately provide the most optimal result. Of course, all decisions should be within the parameter of what is acceptable to your client.

Why Holistic Financial Planning matters

My first car was a 1976 Dodge Colt, and it had a two-stage carburetor, which was fun, and bias ply tires, which were also fun, but in a different way. The tires were far less stable on the road than today’s radials, but they were great in the dirt, and I had a blast driving them off-road. Living in Phoenix as a teenager, we were never far from a desert road, and boy, did my friends and I put our cars through their paces.

One thing I always remembered was a good bit of advice that probably saved me from catastrophe:

When driving a vehicle that is out of control on the road, hold the wheel as straight as possible, let off the gas pedal, and do not press the brake.

This made a lot of sense, and I can say (from experience) that it works.

That’s the way I see today’s process with clients, only the advice they are receiving is to oversteer, slam on the brakes, or press the accelerator. The investing public is starting to see that many advisors and their advice are just as foolish as a driver doing the same thing in a vehicle.

When we stop short of real holistic planning, the picture is seriously skewed, and pushing down on the accelerator leads to all the same outcomes of doing the same thing in a car that is out of control. You can see a short video explanation how holistic planning can add ROI for your clients.

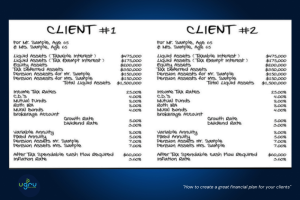

Let me explain. Let’s say there are two clients, each age 65. They are identical in every way possible.

They have the same:

- Accounts and fees

- Rate of returns

- Beginning balances and cost basis on each account[3]

- Income needs and duration

- Inflation rate

- Tax brackets

So, they have the same financial outcome, right?

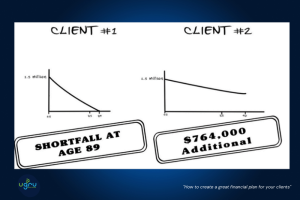

Wrong. Client #1 had a shortfall at age 89. Client #2 had a sustained retirement through age 90 and still had $652,000 left over. When accounting for the money required to fund Client #1 in their last year, the total difference is $764,000. This was accomplished by calculating the most optimal distribution order among each investment.

The main point of this exercise is this: the $764,000 extra is equivalent to a 50% return on the beginning liquid net worth of $1.5 million. Do the math, and that equates to a 2%-per-year rate of return for 26 years where you didn’t have to rely on a higher-performing investment.

In other words, we don’t have to push the accelerator when we find that client #1 has a shortfall; we just have to rework the distribution. There is no way you could have known this without first exercising your planning muscles.

Incorporating how you hold debt, pension maximization, time-segmented distribution, mortgage acceleration, stretch IRAs, Roth conversions, and many more planning strategies into one holistic plan is the only way to plan properly.

Therefore, it’s important to control what you can and manage what you can’t. If you can control the aspects of fees, taxes, and other decisions that have a positive known outcome, this will translate into a return on money. Then, and only then, is it time to consider investment selection.

Performance: More than the next financial product you sell

Performance is far more complex than just evaluating the return on a portfolio. It also involves safeguarding your client’s portfolio in down economies, steering through sideways markets, and most importantly, making decisions today that ultimately affect your clients financial standing tomorrow.

Everyone has their own financial fingerprint, yet almost 70% of client market share is fought over by advisors who arm themselves on the unknown basis of manager performance and fees, further commoditizing themselves and the financial services industry.[4]

This all begs the question: how thorough is your planning process? This question includes your philosophy as well as the tools you use to support it.

Problems with today’s planning philosophy

“Control what you can; manage what you can’t.”

– Unknown

There are two big issues I see with today’s planning philosophy: lack of proper iterative planning and the way historical performance is viewed.

Lack of Category-Iterative Planning

The only way to produce a proper financial plan is to go through a category-iterative process, where your client’s financial life is separated into major categories, like real estate, estate planning, asset distribution, tax planning, etc.

Once each category is identified, an iterative process should begin where you employ tactics that achieve a different outcome in the ending net worth value of the plan. From this process, the most optimal ending trajectory is identified per category and applied to the plan holistically.

The next natural step would be to move on to the next category and apply the same iterative process relative to the new category, being mindful that the most optimal iteration in one category might adversely affect the previous optimization of another category. This process can be difficult and time-consuming, so having the right technology and tools like Retirement Destinations ™ is extremely important.

This is the only way for planners to truly act as a fiduciary for their clients, and it is what is expected of advisors more each day. However, a completely different philosophy is routinely exercised, as I have outlined earlier.

Even worse, the philosophy is exercised through a particular historical performance lens.

Long Term Isn’t Long Enough

“It’s hard to see things when you’re too close. Take a step back and look.”

– Bob Ross, artist

I remember sitting in a seminar in 2003 that an advisor was giving, and he showed the audience a chart of market performance by decade, starting with the Great Depression. He reasoned with the audience that there was, in fact, only one losing decade, which he referred to as both an aberration and an event that was a hundred-year phenomenon, like a hundred-year flood.

The decade he was talking about was the 70s, and he went on to explain that there has never been a sliding ten-year period since or before. Of course, no data was provided before the Great Depression.

I never really thought much about it until late 2007. I had been running five portfolios in my RIA, and I was frustrated that I could not find positive indicators for constructing the portfolios going into 2008. In fact, I was so frustrated that I placed 100% of my clients in cash equivalents that year except for those in an income portfolio. By the end of the year, four things had happened:

- I lost ten million in assets mid-year from clients who had left me because they weren’t happy with my decision.

- Saving the clients that stayed from doom, I waved the banner for all I could get and wound up bringing in another 50 million with new investors.

- I decided that my portfolio management days were over because I realized that I was human, and my decision could have been a HUGE mistake.

- I became intensely interested in researching the markets before the Great Depression.

On the fourth point, I found something that was very interesting. I realized that during the 1800s, each decade or so had a rather large loss. Back then, they referred to these as “panics,” but the pattern of suffering losses as much as 50% each decade came to an end with the Great Depression.

When advisors use the Great Depression as a starting point, I believe it skews the picture because, for nearly five decades after the Great Depression, we had unprecedented prosperity. This ended in 1973 with the oil embargo, which hit a whole new generation with back-to-back market losses greater than 50%. Twenty-seven years later, we experienced the tech bubble, with back-to-back-to-back losses of 50%. Then, seven years after that, the real estate bubble burst, and again we faced this 50% loss in back-to-back markets. And the next is now overdue.

You can see a short video that expands on this thought and shares a great alternative investment strategy I call Destination Trax™ that could help drive more revenue for your financial practice.

The philosophy that advisors have viewed the markets through, and we have been trained on, I believe, is myopic. I don’t believe the “aberration” was the decade of the 70s. I think the aberration was the unprecedented prosperity for fifty years after the Great Depression.

The pattern seems clear to me now that we have seen these 50% losses occur with greater frequency in the last 45 years, and in my opinion, we are going back to the norm of the 1800s, where we should be expecting a shakeout every decade or so.

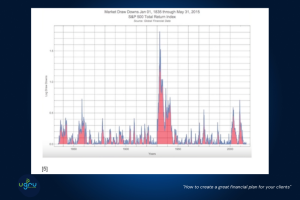

Looking at the next chart, you can easily see the market drawdowns for the one hundred years before the Great Depression were far more active than our modern markets.

Looking at the next chart, you can easily see the market drawdowns for the one hundred years before the Great Depression were far more active than our modern markets.

If you think the past is irrelevant and does not apply in today’s modern era, I would ask: at what point does history hit the “modern” mark? Modern computers weren’t around during the Great Depression, the internet wasn’t around in the 80s, and smartphones weren’t around at the change of the millennium.

I would contend that behavior is at the root of the trading system and that more data does not mean better market behavior. In fact, it could mean quite the opposite. So, I would say the second issue is that advisors and other well-known personalities are too bullish on future returns, especially as applied to financial plans.

Most advisors I speak with say they use relatively low returns when modeling their client plan and feel comfortable with that, but this could prove disastrous.

I explain why in the next few paragraphs, under “Static Returns.” But first, I’d like to share my thoughts on todays software you might be using to help your clients.

Problems with Today’s Planning Software

For the last 11 years of my career, financial planning was my signature service, but finding planning software proved way too difficult. Some were really cool looking and had very professional user interfaces, but they seriously lacked the ability to do some heavy lifting on planning. Some software didn’t even show the difference between tax-deferred and tax-free returns.

I ultimately used software that was open architecture, but I about wore the buttons out on my HP 12C because it just lacked a lot of functionality. I would spend from six to as much as forty hours constructing a quality plan because of this, but I could show an accurate and detailed plan, and that was a priority for my clients and me.

I am not the only one to observe that planning software is ineffective. This is what the Society of Actuaries had to say:

“The majority of available planning software tools still fail to effectively address the wide range of individual issues related to retirement.”[6]

The SOA analyzed 12 financial planning software programs most commonly used by individuals and financial advisors which were available over the internet or designed for use by professional advisors.

After crunching the numbers in the twelve programs, the Society of Actuaries found that:

“planning software needs to better address key planning issues including: Longevity, unexpected events and risks, housing, social security and annuities.”[6]

More recently, Michael Kitces weighed in on this when he said:

“The ability to illustrate specific planning strategies, or the impact of various financial services products as a solution, has remained remarkably limited.”[7]

I could write another book dedicated to just the shortfalls in planning, but to briefly expand on this thought, I will cover two huge and common issues revolving around the use of static returns and Monte Carlo simulation in plans.

Static Returns

When I was in my third year of college math, I remember getting into a very interesting debate over standard deviation. My contention was that advisors (me being one at the time) were assigning static rates to accounts in our planning process and that this couldn’t possibly be serving the client well. I also believed this was likely causing an inaccurate accounting of future projections, though, to what extent, I was unsure.

My professor quickly responded that it was irrelevant how volatile any account was as long as the mean (average) was equal to the static return used in the plan. However, one simple question threw a monkey wrench into what was, of course, mathematical fact. That question was: so, what happens to the trajectory of account values when we treat income needed each year as a variable? This has been part of my life’s work, which is illustrated in a bit, so let me set the stage for what you will see.

Investment outcomes in the real world are the result of a near-infinite set of variables, but advisors should try to create the most real-to-life scenario as possible by including the testing of what I refer to as “Market Dynamics.”

Market Dynamics are compared to the static returns commonly used by advisors in the examples I use.

I have found that the assumptions of static returns can lead to a false sense of confidence as it relates to a client’s future because they create a perfect scenario. I believe that by using a past market that is dynamic in nature, you can more closely align future expectations.

This is done by taking a stretch of historical performance data (like S&P 500 performance from 1970–2014) and overlaying each year through the course of your expected returns. In other words, the performance of 1970 becomes the illustrated performance of your clients first year of the plan, and so on. If the illustrated plan happens to be longer in years than that of the historical data, the original first year of performance then picks up where the data leaves off.

For example, you illustrate 30 years in your plan but choose to use performance data from 2000–2009. In this case, the 11th year of the plan uses the performance of the year 2000 again and continues as it did in the first cycle.

The reports shown in the coming paragraphs are identical (meaning they are the same client) except for the comparison of a static vs. a dynamic environment. The static rates are derived from the same average return found in the dynamic period, which is illustrated separately and comparatively.

All other numbers in each scenario are equal, including fees, inflation rates, beginning account balances, withdrawal rates, tax brackets, and distribution order of each account, so they are compared static against a dynamic environment.

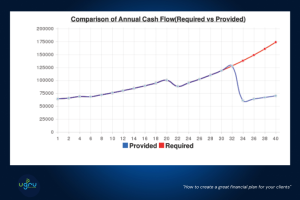

The first chart you see shows average returns (dividends included) in each year of 12.02% (CAGR[8] = 10.49%) with a standard deviation of 17.47%. This is the identical average performance (dividends included) of the S&P 500 from 1970 to 2014.[9]

The first chart you see shows average returns (dividends included) in each year of 12.02% (CAGR[8] = 10.49%) with a standard deviation of 17.47%. This is the identical average performance (dividends included) of the S&P 500 from 1970 to 2014.[9]

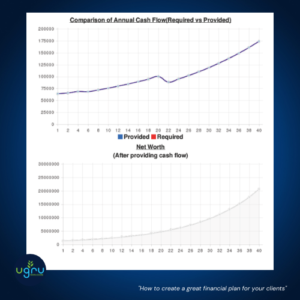

As you can see, the resulting net worth is over $20 million, which would certainly warrant estate planning like a QPRT (qualified personal residence trust) and/or an ILIT (irrevocable life insurance trust). As fun as this sounds to those who offer legal advice or sell insurance, let’s see what happens when we add the impact of the market dynamics overlay on the next chart.

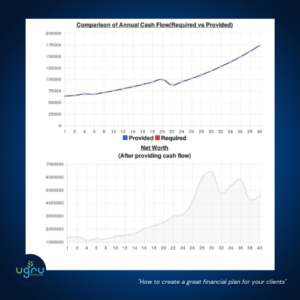

The outcome is dramatic even though the same average return exists in the mix. Now you have an ending net worth less than $5 million, which doesn’t even exceed the available unified credit equivalent by today’s Internal Revenue Code (meaning your client doesn’t have an estate tax problem and you don’t need to sell an expensive solution to a problem that likely doesn’t exist).

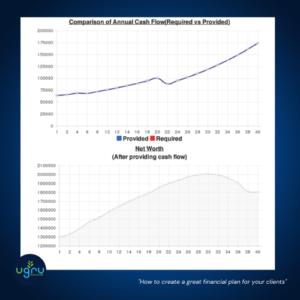

But to be fair, the next chart implies that one should consider the prudence that many advisors claim they take. So, let’s use a static return of 7.35% (CAGR = 5.01%) with a standard deviation of 21.1%. This shows the identical performance (dividends included) of the S&P 500 from 1997 to 2009.

But to be fair, the next chart implies that one should consider the prudence that many advisors claim they take. So, let’s use a static return of 7.35% (CAGR = 5.01%) with a standard deviation of 21.1%. This shows the identical performance (dividends included) of the S&P 500 from 1997 to 2009.

Now you have an ending net worth of $1.8 million. We have demonstrated prudence with conservative performance, and we have something that both the advisor and client can be happy with. That’s more accurate and fair, right? Not exactly.

The first indicator that it’s not accurate is the smooth acceleration and deceleration of net worth. Since when is anything smooth in the world of money?

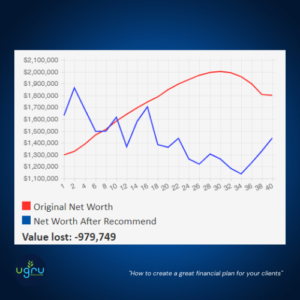

By comparing the previous chart to the application of market dynamics in the chart above, you can see that you now have a shortfall in year 33 of your plan and subsequently zero net worth. Twenty million to broke takes a lot of doing.

What clients are being shown time and again is a beautiful slope that is psychologically easy to swallow, but the reality is the jagged blue line that (in this case) initially performs better because of the tear the market was on in the early years (1997–1999).

But as time rolls on, you can see the effects of volatility as opposed to the beautiful static and conservative returns, even though they are the same average. And the difference of almost $1 million (just comparing the last scenario) is enough to warrant additional work with holistic planning.

Without this understanding, the advisor’s work stops at a seemingly solid scenario ($20 million) that your clients are happy with – at first. Let’s talk about another problematic issue.

Monte Carlo Simulators

LifeLock once ran a hilarious commercial. It opens with a bank robbery, where the assailants are yelling for everyone to get on the floor. A nervous lady looks up at the guy dressed in a guard’s uniform and instructs him to do something, to which he replies, “I’m not a security guard. I’m a security monitor. I only notify people if there is a robbery.” Looking at the robbers and then back at her, he states, “There’s a robbery.”

The point of the commercial asks the same question that could be asked of advisors: “Why monitor a problem if you don’t fix it?”

When an architect draws up plans for a building, they don’t give a probability of whether the building will be built. No, the building is thought out down to the last detail and built by measuring twice and cutting once.

Sure, the owner may make changes to some aspects of the building, like the fit and finish, as the process unfolds, but that doesn’t mean the building has a probability of not being built. So, why do advisors give clients a probability (Monte Carlo) of whether they will plan their successful future? The advisor either will or won’t.

And, no, the answer is not “we are giving probabilities because we cannot guarantee investment outcome”. If that was your thought you haven’t been paying attention to this point. Financial planning is the process of first controlling what you can. Then (and only then) should you consider the things you cannot control (the portfolio allocation).

Monte Carlo is fascinating to me, but there are two main reasons why I decided not to use it with my clients:

- To achieve realistic output, hundreds of inputs need to be accounted for (which are not with Monte Carlo) relative to the client and the spouse, including (but not limited to):

a. Investment distributions

b. Various income needs

c. Possible surplus or deficit in any given year

d. One-time purchases

e. Emergency needs

f. Social Security options

g. Guaranteed income benefit (GIB) variations

h. Income tax

i. Estate tax

j. Capital gains tax

k. Life expectancy

l. Age at retirement

Essentially, what’s available and commonly used as a tool is nowhere even close to cutting it, which makes a potential serious planning tool a novelty of sorts and places us squarely back in the position of having to plan anyway.

2. Monte Carlo makes selling the portfolio or investment the priority.

When you have a tool that assesses each portfolio to project the probability of outcomes, it’s easy to get caught up in what I call “portfolio as a priority,” a dangerous proposition I’ll explain later. When the portfolio is the priority, planning takes a backseat, which is to say that planning is executed only to the extent that gaps are identified, therefore placing focus on the products needed to fill those holes. Advisors know this, and I have seen their behavior change dramatically when presenting to clients.

When advisors know that there are areas that haven’t been given the needed thought, it becomes easier to talk over their clients, which I believe is due to their subconscious covering up the fact that they have offered very little value. It often comes out sounding like this:

Mr. and Mrs. Client, as you can see, I have prepared a Monte Carlo simulation, which is the same intense mathematical theory used in developing the hydrogen bomb. What we are doing is accounting for the “drift,” which is the historical average of the periodic daily returns of your assets eroded by volatility at the rate of half the variance over time.

Time out… What!? It reminds me of a quote:

“It takes a lot of words to cover up a lie.”

Look, it takes more work to take a period like 2000–2009 (the “lost decade”) and use that as an acid test for which an advisor’s time and knowledge should shore up all the shortcomings.

This is why I say it encourages portfolio as priority. The industry we work in wants us to sell our clients their financial products, and it’s been far easier for many of us to speak over our client’s head using a fancy tool that really has no teeth. Besides that, the Monte Carlo simulator:

- Cannot perform the analysis on all accounts for a holistic assessment.

- Cannot demonstrate deep losses.

- Cannot help plan for your clients outliving their money.

- Has a high propensity to use longer periods for a more accurate average, which actually throws the probabilities into unrealistic territory and gives you and your clients a false sense of security.

Why Advisors Don’t Provide Quality Plans

“People pretend not to like grapes when the vines are too high for them to reach.”

– Marguerite de Navarre, French author, 1492–1549 A 2013 survey revealed:

A 2013 survey revealed:

An overwhelming majority of consumers (91%) expect the advice they receive from a financial advisor to “Consider my total financial situation”.

This expectation was largely consistent across all age groups. And no other category of concern came close.[10]

The report of the survey went on to say that more than three to one surveyed preferred their advisors to have knowledge in multiple financial areas, as opposed to specialized knowledge.

There are over 300,000 advisors in the United States, and according to FINRA, there are over 175 designations and certifications available for their higher education.[11] One of the most recognized is the CFP (Certified Financial Planner) designation.

According to the CFP board, they have granted this designation to 76,000 professionals in the United States (as of the time of this writing). I would be willing to bet that they and the other 174 programs combined have issued well over the number of advisors that exist in the US.

So, advisors are seeking higher knowledge, and they are hanging the proof on their walls in a picture frame. Their clients see it, and if they don’t, advisors are likely to point it out at some point in the beginning of the relationship.

According to Cerulli, six out of ten advisors describe themselves as financial planners, yet only 30% truly offer planning services.[12] If so many advisors exist that have been trained in or have a certificate in multiple disciplines and are self-described as providing financial planning services, why is it that they don’t provide quality plans? I would say it’s two-fold:

- Lack of proper tools to provide the plans

- Lack of practice (business) efficiency, which constrains the time needed to construct a quality plan

If you’re interested, I take a dive on point number two in another Blog titled How to make your financial practice successful.

Immediate gratification syndrome drives advisors to seek success in every misdirected behavior they display, but ironically, it’s that same behavior that limits their success.

If you’re focused on adding value for your clients eg. “Creating a great financial plan for your clients”, you must realize your business inefficiencies that prevent you from being of value. Become more efficient and you can better identify and address client issues. If an advisor focuses first on being a person of value, they will have far more success than if they placed their own financial success as a primary target.

Engaging in the financial planning process is critical first step, not only for the clients you serve, but also for the sake of creating a thriving financial practice for yourself.

If advisors were better businessmen and women, they would have more time for their clients. When they aren’t, clients smell it, and when you try to get them to sign paperwork to become your client, they say: “Let me think about it.” I am sure they sincerely mean to think about it, but do they know how?

The financial planning process is a powerful tool for advisors combatting the excuse of “Let me think about it” because the planning process is precisely that – thinking about it.

If you want to step up your game by:

- Getting better results for your clients

- Making more money per client

- Overcoming the “let me think about it” excuse.

- Separating yourself from the millions of other professionals

Then check out our tools and training by clicking HERE.

If you are ready to scale your financial practice, find the benefits UGRU can bring to your current financial practice with our UGRU training program, financial software, marketing, plus all the personal finance courses you could offer your clients to help you generate more recurring revenue.

Feel free to schedule a time or discover now what the UGRU training program and Retirement Destinations™ can do for you.

All the best,

No one knows your business like “U“

Want my newest book for FREE?

Right Where They Want You: Why You're Not Rich and What to Do about It

Whether you are a financial professional or aspiring to be financially independent. This is a MUST listen audiobook!

FOOTNOTES

[1] Such simulations show possible outcomes of portfolio decisions and assess the impact of risk, allowing for better decision-making under uncertainty.

[2]https://finra.complinet.com/en/display/display.html?rbid=2403&element_id=10651

[3] Cost basis is the original value of an asset for tax purposes. This value is used to determine the capital gain, which is equal to the difference between the asset’s cost basis and the current market value.

[4] Cerulli Associates and College for Financial Planning, 2009 Survey of Trends in the Financial Planning Industry.

[5] Ben Carlson. “180 Years of Market Drawdowns” April 24, 2016. https://awealthofcommonsense.com/2016/04/180-years-of-market-drawdowns/

[6] The Network Journal article from 2-15-2011 by Robert Powell.

[7] www.kitces.com/blog/designing-the-financial-planning-software-of-the-future-calculator-collaboration-tool-and-client-pfm/

[8] Compound annual growth rate (CAGR) is a business and investing specific term for the geometric progression ratio that provides a constant rate of return over the time period.

[9] https://www.moneychimp.com/features/market_cagr.htm

[10] CFP Board. “CONSUMERS WANT ADVISERS TO FOCUS ON FINANCIAL PLANNING.” Aug 20, 2013. https://www.cfp.net/news-events/latest-news/2013/08/20/consumers-want-advisers-to-focus-on-financial-planning

[11] https://www.finra.org/investors/professional-designations

[12] “59% of Advisors Perceive Themselves as Financial Planners, But Only 30% Truly Offer Planning Services,” Cerulli Report Press Release, January 19, 2012; Cerulli Quantitative Update: Advisor Metrics 2011.

1 thought on “How to create a great financial plan for your clients”

Good to know!